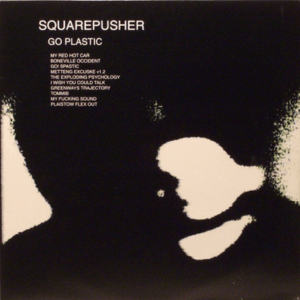

Go Plastic is the 5th album by Squarepusher (6th if you count Budakhan Mindphone as an album, which I don’t). It was released on Warp Records in June 2001. This was a big year for so-called intelligent dance music, with Drukqs by Aphex Twin, Double Figure by Plaid and Confield by Autechre all dropping that year, plus a plethora of what you might call second-tier acts in the scene were also having their moment. Although it feels a little specious to call it a scene, as even though many such artists were grouped under the IDM label, the actual music they created differed wildly. But I digress.

For the creation of Go Plastic, Squarepusher abandoned the live instruments and hardware that he’d employed up to that point and instead went completely digital.

I’ll get this out the way now because it’s going to colour the rest of the review, Go Plastic is my favourite Squarepusher album, always has been and always will be – unless he comes out with an absolute stormer, but it’s hard to see even a late career great being able to compete with the years of enjoyment I’ve had with Go Plastic. There are some artists for whom your favourite album might change depending on mood but not in this case, whenever you ask me, the answer will be the same. For me it’s that rare thing of a perfect album, I wouldn’t change a moment on it, so there we go.

Fundamentally, Go Plastic is a project to deconstruct, and then reform, reimagine and explore the core essence of genres like drum’n’bass, Jungle and UK Garage. And I’d say there are three core elements that define the form of those genres. The first is sampled, edited and processed breakbeats. Then there’s the bass, which doesn’t really require much further explanation. And thirdly there’s the sample pool they draw from, which isn’t strictly delineated but generally consists of reggae, dancehall, dub and hip-hop, which all form the basis of the source material for the best known through to the most obscure samples.

In interviews given at the time, Squarepusher talks about taking breakbeat samples and deconstructing them to a level where he is essentially treating them as an instrument in themselves. Rather than fragments of recording to be pasted together like a collage, these are the very raw materials of his sound: the sine waves, drum hits and bass notes. Thus we get the ultimate realisation of the ambition that was suggested by records like Big Loada and Hard Normal Daddy, where the boundary of rhythm and melody is dissolved. Now percussion, the physical collision of two elements to produce a unit of tempo becomes melody; and melody can be condensed, fragmented and regurgitated to become rhythm.

The result is a bold, experimental record with unconventional structures and an extremely freeform approach. But Jenkinson doesn’t completely abandon the essence of what makes his source material – garage, d’n’b etc – appealing, i.e. it’s fucking banging. Yes this is unpredictable and challenging music but it’s not musical wankery, or stuff to sit and stroke your chin to (not that I’ve got anything against that, in the right context).

It seems silly to start anywhere but the beginning,with the lead single off the album, track 1 – My Red Hot Car. Unlike the rest of Go Plastic, which is formidably uncompromising, MRHC is very much tongue in cheek. Or at least the UK Garage-parodying vocodered vocal and the tacky synth notes are. The lyrics are clearly a nod to the macho, sexualised and often outright sexist lyrics to be found in hip-hop and UK Garage at the time; that combined with the fetishisation of cars as the expression of masculinity. I even remember a CD given away with a lads mag like Maxim at the time which contained tracks composed of ultra low-end bass frequencies and little else, supposedly designed to test out your car’s subwoofer.

So yeah, when Squarepusher croons I’m gonna fuck you with my red hot car – transmogrifying car into cock, he’s definitely not being serious. Nor do I see it as a complete piss-take as such, but a sly dig to say, look I can do your style but I can also do this as the track jumps off from that fairly ‘normal’ opening into what at first sounds like freeform chaos, but is a masterfully executed meander through the underbelly of UK urban music in 2001; a maverick jazz sensibility twisting the dial through a hundred late night pirate radio stations.

After that, we’re into full on insanity for the next two tracks, Boneville Occident and Go Spastic. Each piece is an epic in its own right, insanely detailed and complex and you’re taken on a wild journey that follows its own warped logic that only makes sense in the universe contained within the track. I could listen to these pieces again and again – and indeed have many times – and constantly find new details and flourishes. That first third of Go Plastic pretty much is the pinnacle of where this kind of sample-based, digital manipulation of breakbeats got to.

Picking a favourite on an album as consistent as Go Plastic is hard but one that’s always up there is The Exploding Psychology, which sits at the heart of the record at track 5. It begins, and ends, at a sedate half-time tempo, unlike the manic 180bpm of the first half. And it has an improvisational feel, almost as if the piece is constructing itself in real time, with layers of beats building on another like rows of blocks. Within this cuboid-like structure, Jenkinson creates an awesome sense of space, with beats appearing and disappearing like platforms in an old 2d computer game, and piercing intrusions of harsh industrial sounds shredding across the mix like laser beam fire. Out of this seeming digital chaos, a surprisingly emotive melody emerges, written in liquid mercury, which closes out proceedings as the beats gradually disassemble themselves and a feeling of ultimate resolution is reached.

I could go on about this track; it’s got this spacey/anime/digital feeling, as well as a strong narrative arc; it feels like Future Garage years before that genre was even a thing. A real high point in the pusher discography.

Following the album’s midway point, I Wish You Could Talk is the first time Tom plays it relatively straight on Go Plastic, taking a sparse breakbeat with minimal adornment or rhythmic manipulation. The sombre melody that builds in the background repurposes the classical piece, Pachelbel’s Cannon, to quietly devastating effect. The template of jungle and drum’n’bass had been put to many uses by 2001, to deploy dancefloor chaos, to induce fear, awe, euphoria, to make people move, groove and chill…but rarely to create bleak, moody epics on this kind of scale, which shares more vibe-wise with artists like Mogwai or Godspeed You Black Emperor.

After that relative palette cleanser, it’s back to deconstructed junglist chaos on Greenaways Trajectory, and even Tom Jenkinson seems to run into a deadend at one point, crushing the breakbeats into a buzz of pure distortion that is doubled over on itself until it gradually dissipates in a hiss of white noise.

Finally, listeners are treated to some genuine respite at track 8, Tommib – which found a wider audience when it was featured on the Lost in Translation soundtrack. It’s just over a minute of soothing echoey chimes – I guess straight up piano, fed through some kind of effect – and it’s the only real moment of peace on Go Plastic. There’s another short interlude at track 4, Metteng Escuske v1.2 that breaks up the first half of the record, but it’s more an execution of tension and release, by means of crushed digital noise and the sound of a bell being struck – rather than any real respite or succour.

The final portion of the album is less of a white knuckle thrill ride and more experimental. My Fucking Sound, presumably references My Sound from Music is Rotted One Note, Squarepusher’s take on avant garde jazz fusion. In my video covering that album, I talk about how that particular track is my favourite from that record, although it’s not representative of the general sound or approach of that album, being more melodically and rhythmically accessible.

My Fucking Sound on the other hand is 7 uncompromising minutes of breakbeats knotted so thoroughly it’s like hacking through 7 foot high brambles, every now and then this is punctuated with incredibly tactile sounds, as some digital signal morphs into the sound of a plastic cup being flicked – like hallucinating household objects out of a cloud of static. Latterly we hear the man himself amid clouds of noise reminding us that he’s the “fucking daddy” – a call back to his 97 track, Come on My Selector and thus creating something of an in joke.

Finally, in the interests of thoroughness, I should mention Plaistow Flex Out, which rounds off proceedings in a more gentle fashion. Jenkinson lays down a boom-bap style beat and a kind of smoking weed at 3am in a parked car vibe, before flexing out with his bass guitar. At least, I always assumed it was his bass guitar, heavily treated and processed, that creates that very distinctive sound of plucked vibration.

Even by Squarepusher’s standards, Go Plastic is an unforgiving and relentless record – and not one you’re likely to enjoy unless you already feel at home in this dystopian post-urban music deconstructed sound world. But this harshness is tempered by a restless sense of exploration, creativity and ultimately, fun. Whenever I put Go Plastic on, I know I’m not gonna be thinking about anything else for the next 45 minutes. There’s so much detail, every second of sound has been laboured over to the nth degree, there’s not one dull moment on the whole record.

And even though this is my favourite Squarepusher album, I don’t see it necessarily as the only high point in his career. He’d go on to create equally – if not more – impressive and original music, and you can check out more of my videos on those albums on my Youtube Channel. But Go Plastic is a super-condensed hit of a very specific sound, and one could argue Squarepusher effectively exhausted that avenue of exploration with the creation of this album. But electronic music producers are nothing if not creative with their constant recycling of samples so Go Plastic is by no means the last word on anything.